Red alert: Record-high ocean temperatures

Our most important natural climate control system is in danger: The oceans are heating up more intensely and rapidly than ever before. In addition, this year could see the El Niño weather phenomenon – with potentially severe consequences for humans and ecosystems.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) sounded the alarm on May 17, announcing that one of the coming five years will very likely be the warmest on record. As a result, the average global temperature over an entire year could for the first time exceed pre-industrial levels by 1.5 degrees.

According to the WMO, the impending record-high temperatures are being driven by further increases in greenhouse gas emissions, but also by the El Niño weather phenomenon. El Niño phases occur in the Pacific every two to seven years and have far-reaching effects on the global climate. For example, they lead to heavy rainfall and floods in western South America and droughts and forest fires in Australia. In early May, the WMO announced that there is a likelihood of 70 percent that an El Niño will develop between June and August and of 80 percent between July and September.

Oceans: Important climate buffers

Temperatures on land and at sea are already rising, but El Niño could drive them even higher. The University of Maine in the United States measured a new record high of 21.1 degrees for the global average sea surface temperature in April. That exceeds the previous record of 21 degrees from 2016, which was the hottest year since record-keeping began.

The oceans have an important buffering function for Earth’s climate. Over decades, they have absorbed approximately 25 percent of the CO2 emissions caused by humans, thus preventing even more rapid global warming. Our oceans also store most of the additional heat that stays on Earth because of the human-induced greenhouse effect. A study in the journal Earth Systems Science Data showed that the oceans absorbed up to 90 percent of this heat between 1971 and 2020.

“So far, the oceans have been working like giant cooling climate control system. But this climate control system is slowly overheating,” says Thorsten Reusch, who heads the Marine Evolutionary Ecology Research Unit at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel. “After that, things will get rather uncomfortable in the oceans and on land as it becomes increasingly difficult to buffer temperature spikes.”

As a result, there will be more and more heat waves on land and in the oceans, Reusch says. “In absolute terms, heat waves in the oceans are not as extreme as on land, but tend to last longer and cover much larger areas, so that many marine organisms cannot escape them.” In its 2019 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) showed that the frequency of marine heat waves has doubled and their intensity has increased since 1982. Two degrees of global warming would cause their frequency to increase 20-fold, says the IPCC.

Impact on ecosystems

According to Reusch, temperature in the oceans work like a master regulator. “It affects nearly all biological processes from their biochemistry to entire ecosystems.” As a result, there will be profound and rapid structural changes in marine ecosystems over the medium to long term. “Species that can move with their shifting climate zones will do so. They are already doing that now. Others will be left behind and, in extreme cases, will suffer local extinctions,” Reusch says.

Global oceanic warming can lead to mass extinctions in kelp forests, trigger epidemics among species essential to ecosystems like sea stars and accelerate coral bleaching in many marine regions. The extreme Mediterranean heat wave of 2022 caused huge populations of sponges, gorgonians, red corals and other species to die off, Reusch states.

“This rise in temperatures is especially problematic for the tropics because many organisms there are already at their physiological limit. However, it equally affects the poles where organisms are very temperature-sensitive and are unable to migrate to higher latitudes.”

Consequences for humans

Since the oceans can absorb large amounts of heat due to their enormous mass, it will take centuries for them to completely warm up way down into all depths. Warm water expands, contributing, along with melting polar ice, to the rise in sea levels. That means the global rise in sea level can go on for several centuries, even if no more greenhouse gases are emitted. This is a direct threat to millions of people living in low-elevation coastal regions and in small island countries.

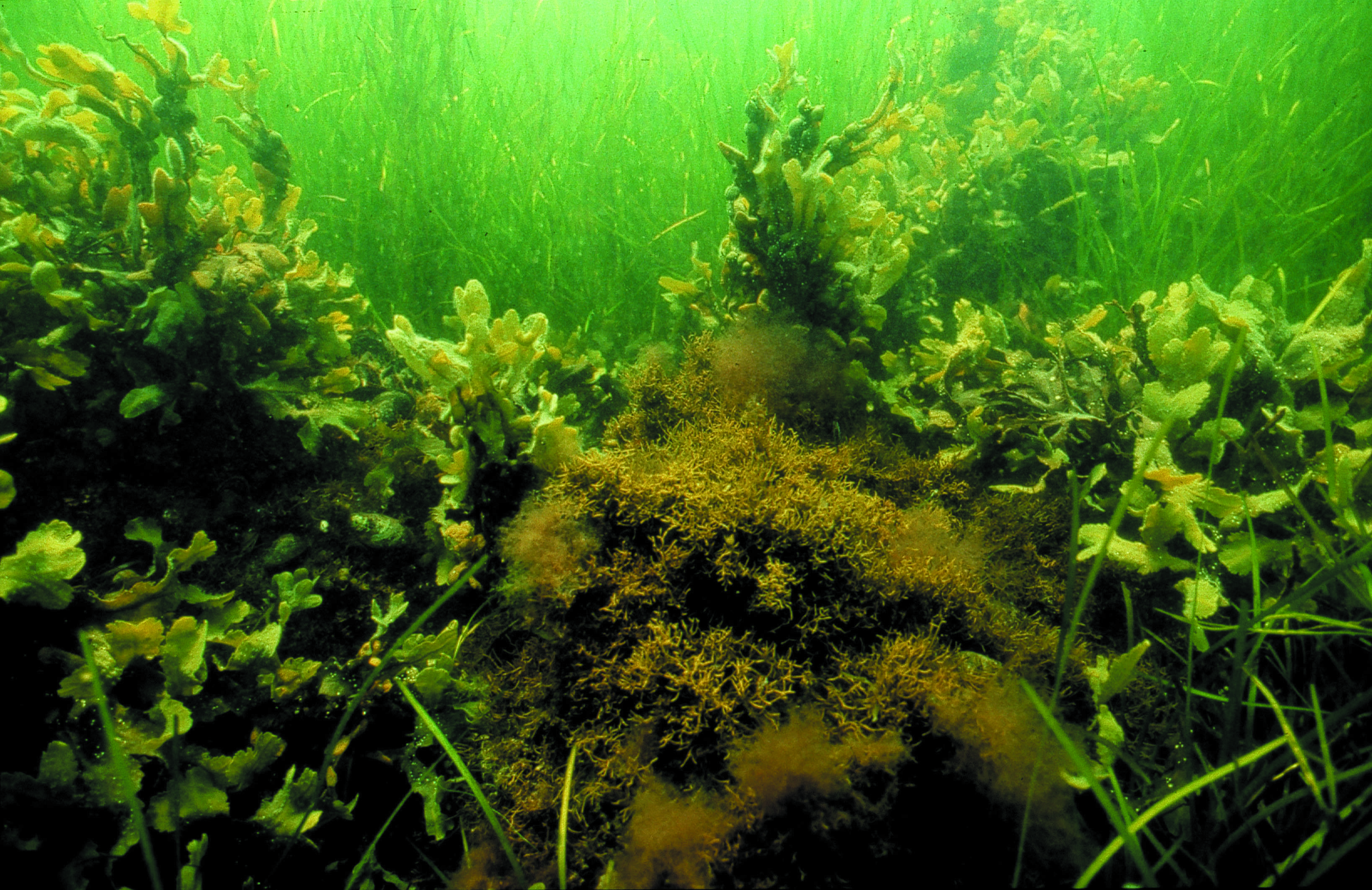

Warming also endangers the important ecosystem services oceans provide for humans. Around half of the oxygen in the atmosphere, for example, is produced by photosynthesis in marine plants like algae and sea grass. Fish and other seafood comprise an important part of the human diet. Mangroves, sea grass and corals help protect coasts from storms and floods. There are also consequences for human health: “For instance, warm water above 25 degrees can harbor many more potentially dangerous bacteria,” Reusch says.

To prevent further warming of the oceans and limit its serious consequences, humanity needs to act quickly, according to Reusch. In his view, it is important now to achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions quickly while applying carbon capture and storage (CCS) as well as nature-based solutions for CO2 storage. “But even if we do meet the Paris target, we will not immediately stop in our tracks. It will take a long time for warming to slow down. That means we also have to adapt to more frequent regional extreme events in the oceans,” Reusch adds.